To view this page in another language, please click here:

Other Languages

The Tarahumara of Chihuahua

ImagesNo Rain Again This Spring in

the Sierra Tarahumara

fter Six Years of Drought

Tarahumara's Facing Desperate Situation

Canyon of the Tarahumara

Copper Canyon Photos

Copper Canyon Trip - 1998

Drug Lords vs. Tarahumaras

For the Love of a People

Fundacion Tarahumara

Land of the Tarahumaras - 1996

Not All Mexicans Speak Spanish

Raramuri of the Sierra Madre

Raramuri of the Sierra Tarahumara

Rararumi Runners in U.S.

Semana Santa Raramuri

Six Racers Are Running for Their Lives

Starvation, Isolation Killing Children of Mexico Indians

Tarahumaras: an Endangered Indigenous Group

Tarahumara Are Survivors

Tarahumara Feats Inspire Awe

Tarahumara: Pillars of the World

Tarahumara medicine, part 1

Tarahumara medicine, part 2

Tarahumara Peoples

Tarahumara: Racers Against Time

Tarahumara Religion/Ceremonies

Tarahumara Society

Tarahumara: The Footrunners Live On

Tarahumara

Vessels

Tarahumara Victim of Mental Health System

Tarahumara Village Leader and Master Carving Artist

Tesguino

and the Tarahumara

El indigena de Chihuahua habla con voz de muerte

by Victor M. Mendoza

According to the legend of the ancient dwellers of the sierra, the world was created by Rayenari -- Sun God -- and Metzaka -- Moon Goddess. In their honor, in the present times they dance, sacrifice animals and drink tesguino. There where the Sierra Madre Occidental becomes rough and uneven, the Tarahumaras, who call themselves Raramuri (Light Feet), live. They had arrived there seeking refuge after the arrival of the Spanish.

The most important activity among them is growing corn and bean and some raise cattle. Due to the fragility of their economy some look for work in the wood mills. The life of this group has changed; the ancient Raramuri had a balanced diet, besides eating regional fruit and vegeta- bles, they hunted wild animals. In the present, industrialized products in their diet might not provide them with all the nutritional ingredients. Other problems the Raramuri have to overcome are caciquismo, closing of woodmills, diseases and epidemics, famine, starvation, and forced labor by mariguana growers, etc.

At present, the Tarahumara consititute the largest indigenous group in the state of Chihuahua. The number varies from 50,000 to 75,000 although is difficult to determine precisely because of the inaccessibility of the mountains, and the deficient communication links. The Tarahumaras are spread in the municipalities of Guerrero, Bocoyna, Ocampo, Uruachi, Chinipas, Guazapares, Urique, Morelos, Batopilas, Guadalupe y Calvo, Balleza, Rosario, Nonoava, San Francisco de Borja y Carichi. The mountainous region is divided in two large regions called Alta and Baja Tarahumara, corresponding the first to the part dominated by the Sierra Madre Occidental dominates and the second to the area west of the same sierra, including the zone of the canyons that forms the warm lands of the state.

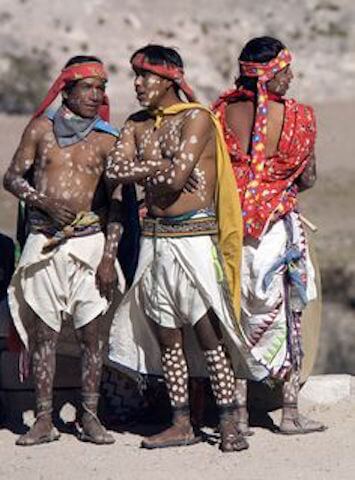

The men are svelte, with strong muscles, recognized as the best long distance runners. The women are shorter, with oval faces, black and oblique eyes and straight nose. The men wear a hairband known as "kowera", huaraches, and loose shirt. The women were a wide skirt and loose blouse, the hair usually covered with a shawl, and a wool waitband known as "pukera".

Their language is sweet and with abundance of words referring to customs and their environment, with polite words like: "I greet you, as the dove that warbles, I wish you health and happiness with your loved ones."

Each house has a hearth and in the bowls they make they cook maize and beans that were harvested during the season. Among the Tarahumaras everything belongs to everybody, private property does not exist, so they share food and housing. They elect a governor - a man who distinguishes for his services to others and his intelligence -- who in turn elect gobernadorcillos: priests, shamans, and sages. These go all over their correspoding towns preaching the pride of being Raramuri, the customs and morals to uphold; function as judges in problems and are in charge of prayers.

Fiestas and Ceremonies

All the commercial liquors are used for fiestas and ceremonies in most places, but the more primitive groups make their own ritual drinks. Among the Huichols and Tarahumaras of the northwest it is a corn beer called tesguino (batari).

As for clothing, there are innumerable styles of serapes of beautiful texture and very simply adorned, that are never seen except on the backs of natives. Notable among these are the tarahumara serapes, heavy and roughly woven, of natural wool colors, mostly unadorned, which possess that peculiar beauty derived solely from texture and simplicity.

A similar trade relationship to the compadres exists among the Tarahumaras, but the participants are called morawas instead of compadres, meaning in their language the joining together of two people who have traded together. When the goods are cattle, the buyer and seller touch each other's shoulder, saying, "Dios cuida morawa," "God protect the morawa." And when one morawa visits another, the guests will be honored with a stool or goatskin to sit on in a preferred place near the fire.

There is always a great deal of reserve between the sexes, especially in the conservative groups. Among the tarahumaras and many others, a man calling at the home of a friend will make his presence known before approaching the door of the house, and if the woman is alone he does not enter but remains at a distance. Unless there is a close relationship, men and women generally talk to one another only when necessary and then at a respectful distance with averted faces.

Tarahumara Dances

The simple primitive dances of the tarahumaras are still vehicles for all their prayers. There used to be the rutuburi and yumari, but now both are combined in the dutuburi, which is danced at all fiestas, on all ceremonial occasions, as well as for curing the sick and dispatching the dead. All Tarahumaras have dance patios near their huts and are constantly giving small and big tesguinadas -dancing, drinking, and praying parties. To make the prayers effective, an animal must be sacrificed and his blood offered to Father Sun, who commanded the people to dance.

Men and women take part in the dutuburi but dance separately. The women line up to the right of the chanter, each one holding the left hand of the one in front with her right hand, and perform a skipping step which begins with the left foot and ends on the right in a slight hop and stamp. They dance back and forth and form an arc, while the men walk forward and backward with the chanter. The chanter repeats a simple refrain to the steady shaking of his rattle, continuing his singing even when the dancers stop to rest for long intervals during the night.

This dance is always performed out of doors, so that Father Sun and Mother Moon may witness it, and near three crosses, because the dancing and singing is directed to them as well. Another small cross is placed at the edge or just outside of the patio when the dutuburi is being danced to ward off sickness. When food is placed on the altar, a small vessel of it is put near the cross with the formula, "Sickness is going to eat; after eating it will go away."

The peyote dance is also simple but a little different. About ten men and women take part in it. The women are led into the dance patio by the two assistant chanters, the men following. Then all dance around a fire to a tune played on a violin and guitar, at intervals slapping their mouths and shouting.

The Tarahumaras also have pascola and Matachine dances, which they had adopted at some time in the past, and always perform at Catholic fiestas. The pascolas wear the same rattling tenabari and jingling belts and do clogging steps like those of the Yaquis, but there the resemblance ends. On Friday of Holy Week at Samachique one lone pascola, accompanied by two little boys, enters the church to dance in the four directions and then continues to the music of a violin and guitar in the convent patio, where he is given food and tesguino. Later another pascola may join him. The pascolas also dance for the dead.

The Matachines dance in greater numbers and seem to be more important, their organization and costumes differing in the various villages. Those of Samachique dress more elaborately than others. They wear a red cloth cape with a blue or white lining, reaching to the knees, over an ordinary white cotton shirt; two pairs of trousers, the red outer ones cut so at the knees that the white pair shows bagging; a belt from which hang red bandannas in front and back; long colored stocking and real shoes of any kind available. The crowns made of thin wood or bark and the arch formed of curved sticks are covered with colored paper, mirrors and other shining things, and fitted on the head over a red bandanna tied under the chin. In the right hand they carry a rattle and in the left an adorned wooden wand.

The dance formation and steps are similar to those of the Yaquis. They also have a monarca, who stands in front between the two lines and indicates all the movements with his wand, and all the dancers beat the rhythm as they form their figures to the music of violin and guitar.

The Tarahumara Matachines are not organized like the Yaqui, but in Samachique each dancer is in charge of a chapeon, who stands to one side of him, marking the rhythm of the dance and shouting the changes in figures in falsetto. The leader of the chapeones wears a wooden mask on the back of his head, painted in white lines, with false white hair and beard. This man holds a position of respect in the community; he often dedicates the tesguino at fiestas and sits with the judges when they are trying offenders.

There seems to be no explanation as to why these men are called chapeones, unless there is some remote relation between them and the capeos, Spaniards who used to fight bulls without weapons at certain fiestas. In New Mexico there are chapeones under different names, who pantomime bullfighting in the Matachine dances.

The name matachin is also of Spanish origin. In ancient times it was applied to gay masqueraders, wearing masks and long vari-colored robes, who danced and made merry, dealing blows with wooden swords and bladders filled with air. But those are a far cry from the Matachines of today in their ritual dances.

The mitote is their sacred instrument and is played only for the corn rites. The players are generally old medicine men. One from the village of San Francisco, Nayarit, said that the mitotes are made by God in heaven and sent to earth; that he knew how to play at birth because God had taught him. But his father and grandfather had been mitote players. The fathers teach their sons music, as all the other arts.

For more information about the Tarahumara, contact:

Delegation INI Chihuahua

Coronado 1413

Col. Sta. Rita

Chihuahua, Chihuahua

Mexico Fundacion Tarahumara -

Jose A. Llaguno, A.B.P.

Daniel Zambrano 518-8

64030 Monterrey, N.L.

México.

Tel. y Fax: Monterrey N.L.: (528) 347 5299

Fax: (528) 346 3977

Cd. de México: (525) 641 4973

FICINA PRINCIPAL

Daniel Zambrano

# 518-Depto. 8 Col. Chepe Vera

Monterrey, N.L. 64030

Tel: (918) 347 52 99 Fax: 346 39 77

OFICINA

MEXICO

Prol. Niños Héroes # 259

Tepepan, México, D.F. 16070

Tel. y Fax: (915) 641 49 73

References:

"Mexico's

Sierra Tarahumara: A Photohistory of the People on the Edge",

by W. Dirk Raat and George

Janecek (1998), Univ. of Ok. Press.

Article in the MAGAZINE entitled "Wooden Promises".

Bernard

L. Fontana, Tarahumara,

Where Night is the Day of the Moon, University of

Arizona Press .

John G. Kennedy, Tarahumara of the Sierra Madre, AHM Publishing.

"The

Tarahumaras: Mexico's Long Distance Runners",

National Geographic, May 1976.

M. John

Fayhee, Mexico's Copper Canyon Country,

A Hiking and Backpacking Guide to Tarahumara-land, Cordillera Press.

![]() Return to Indigenous Peoples' Literature

Return to Indigenous Peoples' Literature

Compiled by: Glenn Welker

ghwelker@gmx.com

This site has been accessed 10,000,000 times since February 8, 1996.